The What, When, Why And How Of Restorative Yoga

Iyengar yoga is an adaptive practice that can be active and vigorous, or restorative and more reflective in nature. A restorative practice involves a sequence of poses that are held for a longer period of time. Props are often used to reduce the exertion required to hold them. Finding a balance between active and restorative is necessary for a well-rounded and sustainable on-going yoga practice routine. In this post it will be explained why a restorative practice is beneficial and why a balance between active and passive is required, what postures constitute recuperative poses, and a sequence to self practice.

Active Before Restorative

Although restorative poses may seem easier because the effort required to do them appears less, in the Iyengar tradition, assuming one is not dealing with illness or injury, a fair degree of experience with dynamic poses is considered necessary before restorative poses are widely practised. Initially one's learning and practice is weighted heavily towards active postures so the body and mind gets energised and cultured through the working of poses dynamically and with attention to detail. The skill and proficiency gained from this work enables restorative poses to be performed with intelligence and integrity, and for their subtle effects to be savoured. Without the invigoration of body and refinement of the mind from a well established active practice a restorative practice can breed dullness and dormancy.

Benefits Of Restorative

A practice that is always active and dynamic can be difficult to sustain on a regular basis and can generate an egoistic temperament in the practitioner. A less rigorous, more restful practice soothes the nervous system, pacifies and calms the mind, and leads to mental clarity. Long holding of poses allows for the deeper physiological effects of the positions and stretches to absorb in. Letting go of the need to strive enables the mind to be in the present and in a receptive space. Such effects and qualities need to be cultivated as one progresses and matures as a yoga practitioner.

Why A Balance Between Active And Restorative Is Necessary In Yoga

According to yoga philosophy everything in the universe - all materiality, or prakrti - is made up of a combination of three fundamental elements, called gunas. They are known as tamas, rajas and sattva. Tamas is the element of earth, darkness, heaviness, inertia and ignorance. Rajas is the element of fire, energy, movement, action and restlessness. Sattva is the element of purity, harmony, lucidity, luminosity and insightfulness. While this may be a difficult concept for one to conceive of, these forces weave together to form the universe and everything in it. They underlie matter, life and mind, as prakrti includes all that is psychological as well as material, all that is intangible as well as tangible. The gunas apply to all that is seen, all that is in our physical framework, and all that is in our psychological makeup.

While tamas and rajas have their positive manifestations - tamas can provide stability, while rajas provides impetus - it is cultivating the quality of sattva in our minds, or citta, which leads to a yogic state. Just as it is necessary, as mentioned above, to cultivate an active practice in the beginning, it is initially essential to cultivate rajas to generate will-power and proceed on the path of yoga. Ultimately, however, one is attempting to increase sattva at the expense of rajas and tamas, and it is the restorative poses that bring out this psychological quality within us.

Aside from the gunas, the Yoga Sutras speak of two essential pillars that need to be developed in one’s practice for it to truly be a yoga practice. Initially there is abhyasa, which literally translates as practice. This is the art of learning through the cultivation of disciplined action. It requires effort and willpower, and can be equated with an active asana practice. Over time vairagya, which translates as renunciation, or restraint, needs to be introduced. It requires a quality of surrender, letting go of the strive and effort to achieve, the ability to observe oneself, and to ultimately draw the energy generated from abhyasa inwards to refine the senses and cultivate discernment and wisdom. In our asana practice this can be equated with the effects gained from a considered restorative asana practice.

BKS Iyengar describes the need for a balance of abhyasa and vairagya in one’s practice in the following way: 'Practice is a generative force of transformation or progress in yoga, but if undertaken alone it produces an unbridled energy which is thrown outwards to the material world as if by centrifugal force. Renunciation acts to sheer of this energetic outburst, protecting the practitioner from entanglement with sense objects and redirecting the energies centripetally towards the core of being.'

Restorative Poses

There are six main restorative poses in Iyengar yoga. All six are based around the inversions, or sirsasana (headstand) and sarvangasana (shoulderstand). Again, according to yoga philosophy, In our usual everyday activities we mostly draw upon the solar system of the body, which relates to our sympathetic nervous system, stimulating our flight or fright response. Inversions are considered to be restorative because they activate the lunar system of the body, which relates to the parasympathetic nervous system, restoring the body to a calm and composed state. See BKS Iyengar explaining this at a demonstration in Sydney in 1992 here. So while there may be other poses that, especially with the support of props, can be considered restorative in nature, such as some of the supine poses and forward bends, the following 6 poses constitute the main restorative poses in the Iyengar system:

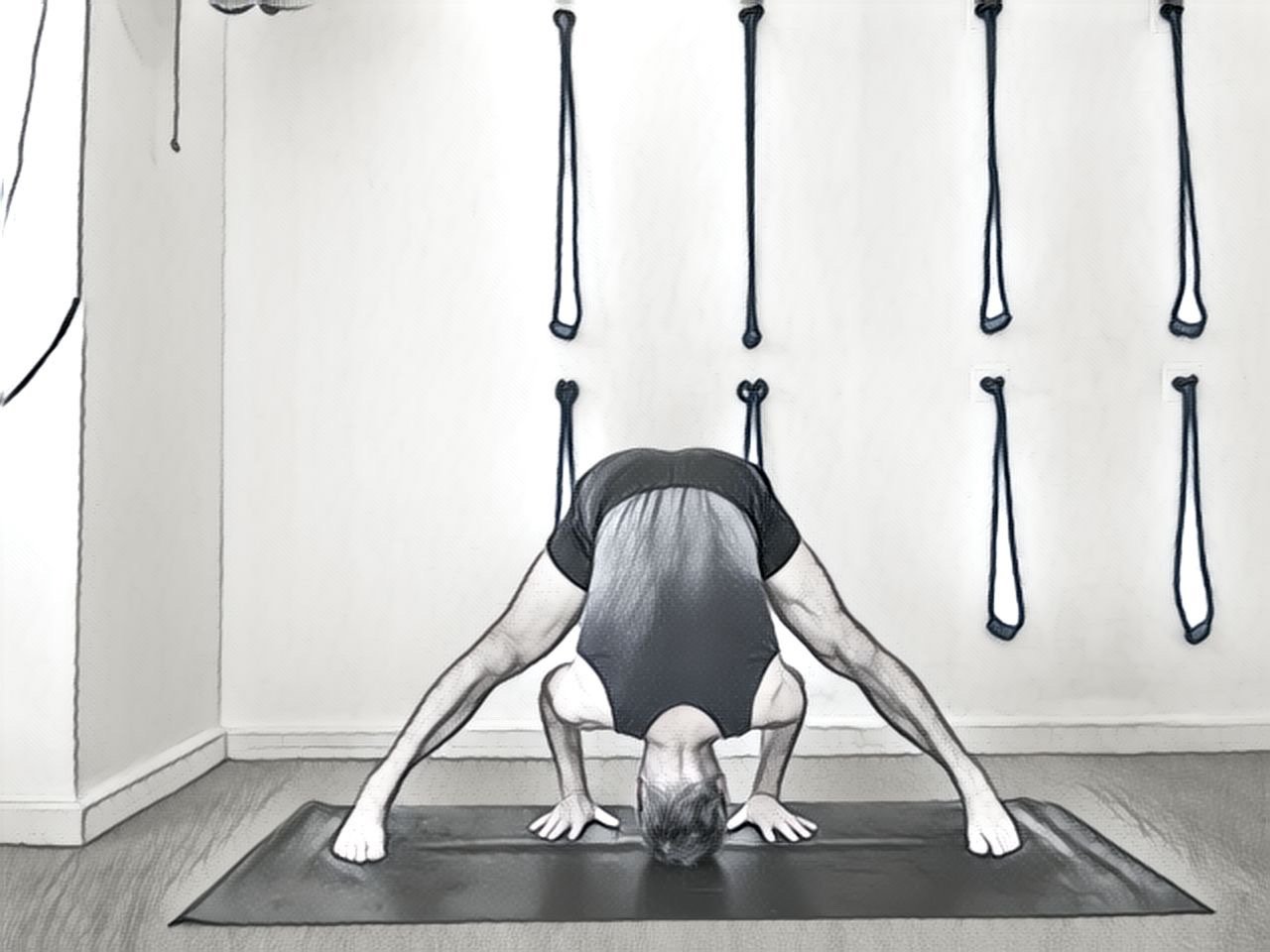

1. Salamba Sirsasana

When one is a seasoned and proficient practitioner, this can be taken independently for 10 - 15 minutes . Alternatively, it can be modified with the use of props. Most commonly it can be taken hanging from wall or ceiling ropes, or between two chairs. Otherwise supported adho mukha svanasana or prasarita padottanasana can be taken. Supta virasana would also be considered an acceptable alternative.

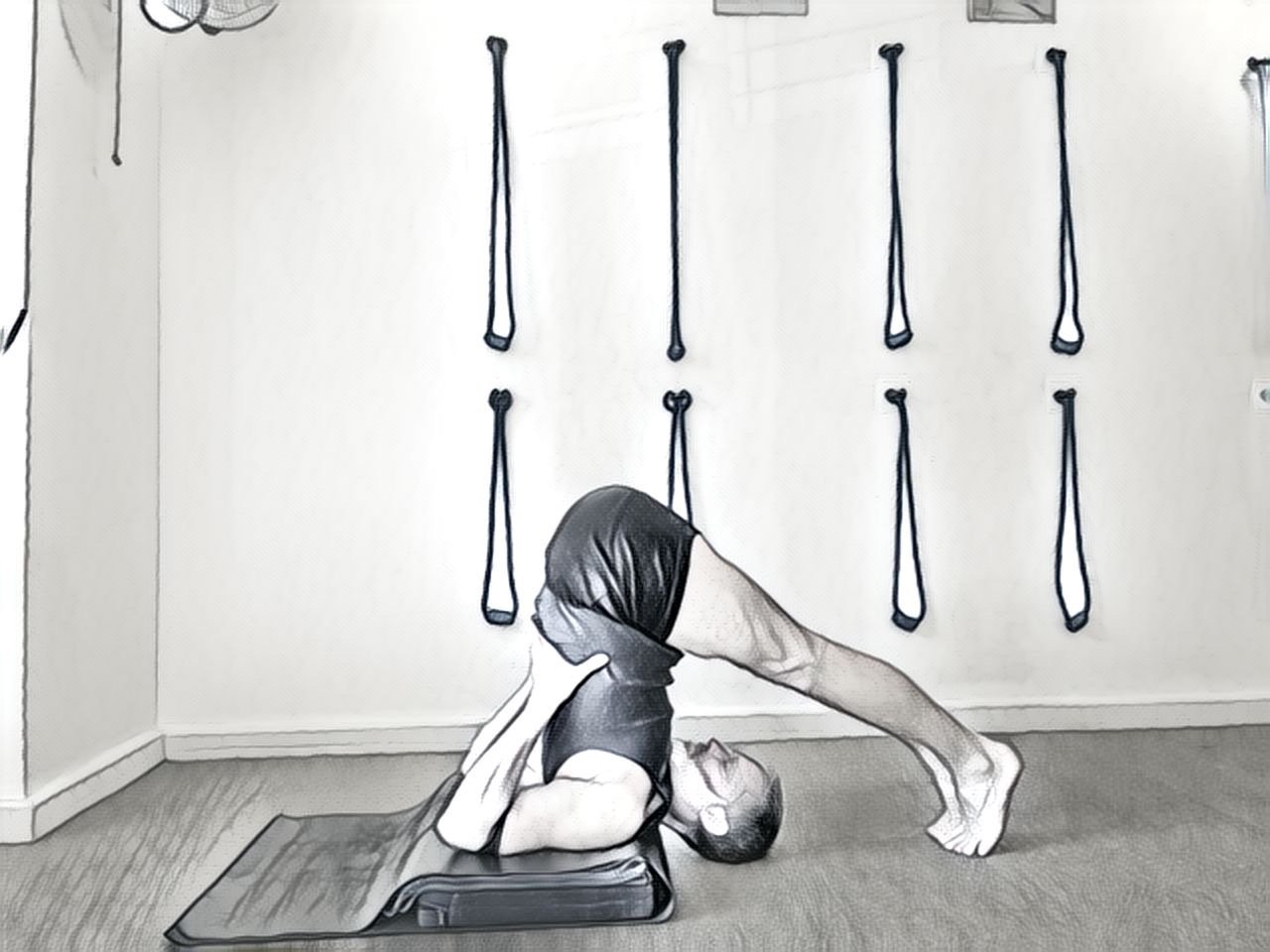

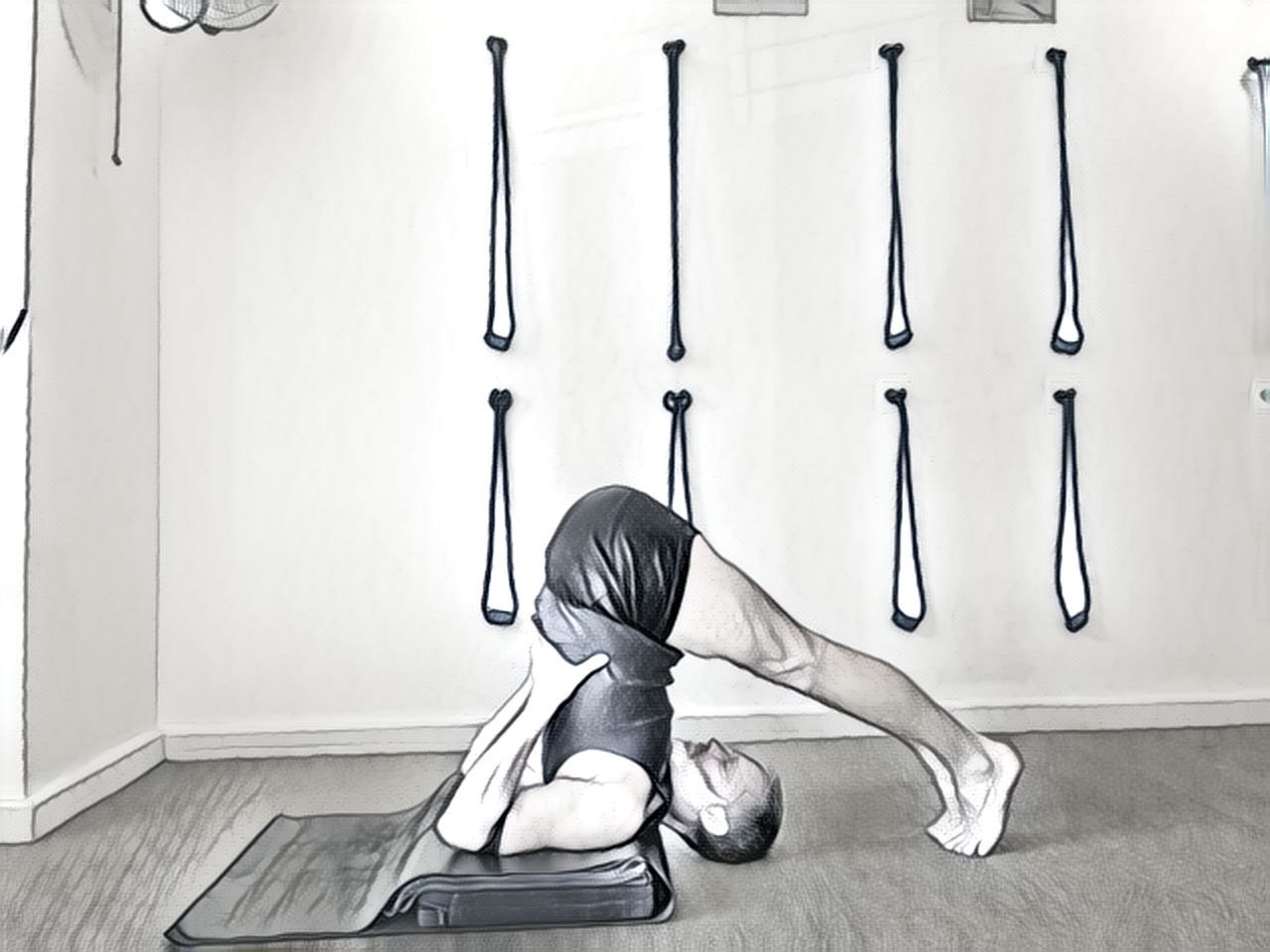

2. Dwi Pada Viparita Dandasana

This is the backbend version of sirsasana. When held in a restorative manner it is taken with the support of a chair. A version of ‘cross bolsters’ where the head is held in a vertical orientation can be done as an alternative. This pose can be held for 5 - 10 minutes.

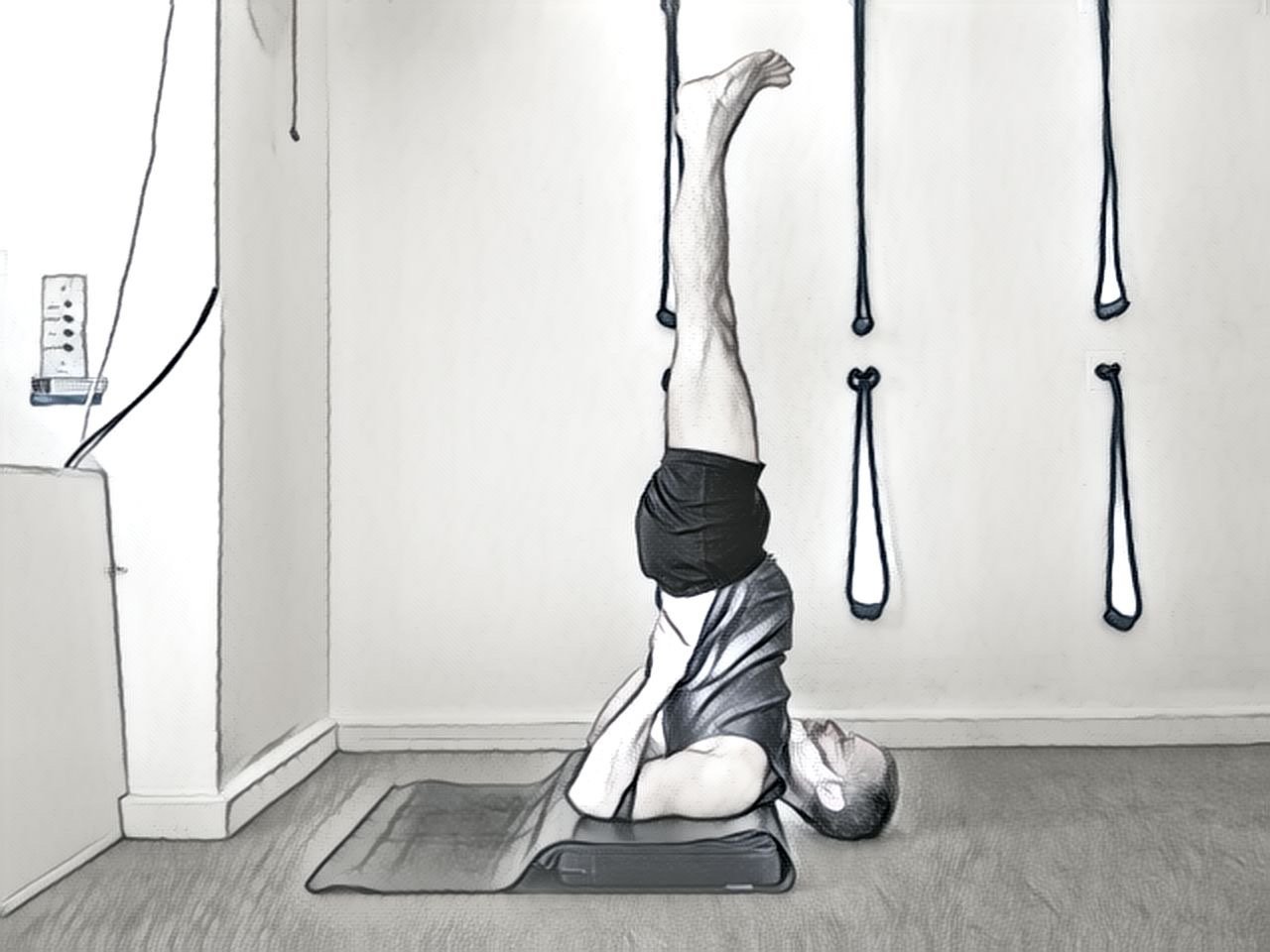

3. Salamba Sarvangasana

As for salamba sirsasana, when one is a seasoned and proficient practitioner, this can be taken independently for 10 - 15 minutes. Alternatively, it can be taken with the support of a chair.

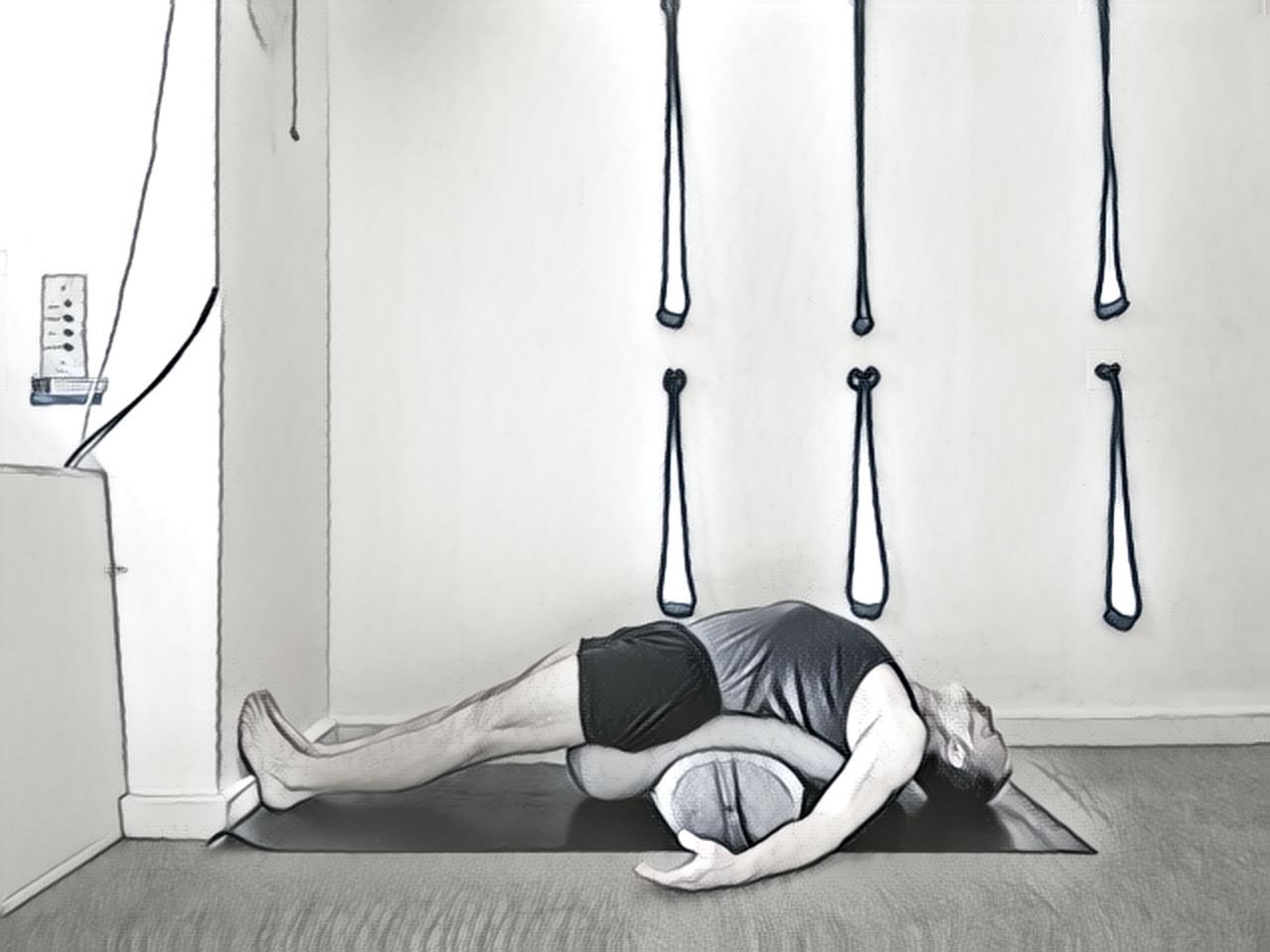

4. Setu Bandha Sarvangasana

this is the backbend version of sarvangasana. It can be taken independently, or in a modified manner using a viparita karani box or brick under the sacrum. Otherwise a version of having a thick bolster, or two stacked bolsters, or combination of bolsters and/or folded longways blankets, perpendicular from a wall can be taken as an alternative. The head, in this variation, needs to be horizontal with the floor. This pose can be held for 5 - 10 minutes.

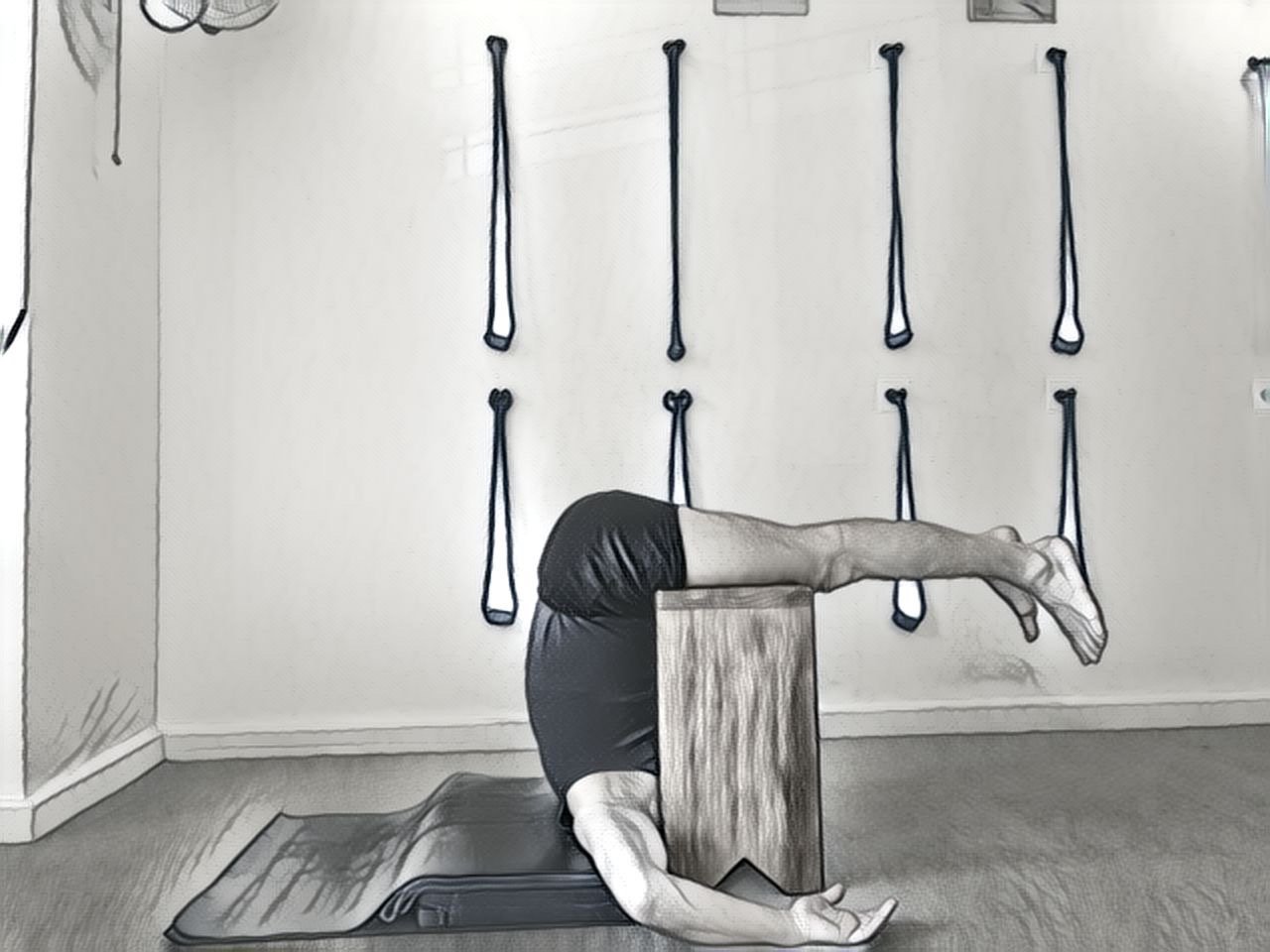

5. Halasana

this can be taken independently, with the feet supported on height, or with the thighs resting on a halasana box or chair supported equivalent. It can also be done with the shoulders on a bolster and the back facing a wall (for easy transition into viparita karani. This pose can be held for 5 minutes.

6. Viparita Karani

This can be taken independently on a viparita karani box, or with the support of bolster(s) or lengthways folded blankets and the backs of the legs resting against a wall. This pose can be held for 3 - 8 minutes.

A restorative sequence, in the order the poses have been presented above, could be done over a 60 - 90 minute session. The sequence could begin with a 3 - 5 minute supported adho mukha svanasana, and conclude with a 5 - 10 minute savasana.

Click here to download a PDF of the full restorative sequence

Attend a mixture of active and restorative classes at our school, in-person or online.

James Hasemer

James Hasemer is the Founder and Director of Central Yoga School and a Senior Iyengar Yoga Teacher, Assessor, and Moderator. He is also currently a Teacher Director on the Iyengar Yoga Australia Board.

References

Light On The Yoga Sutras Of Patanjali BKS Iyengar